Tiran Bajgiran is a student at Harvard Law School.

“If hard work were such a wonderful thing, surely the rich would have kept it all to themselves.”

— Lane Kirkland

Is a worker revolution quietly brewing in cyberspace?

The Covid era has witnessed unprecedented grassroots mobilization of workers on digital platforms, who are finding community in pushing back against exploitative employers. Common to these scattered online movements is a rejection of the centrality of work as an organizing cultural and societal principle.

On Reddit, the r/antiwork forum saw a 500% growth in subscribers through the pandemic, reaching 1 million self-proclaimed “idlers” committed “to start a conversation to problematize work as we know it”; and to resist a culture that values “the needs and desires of managers and corporations above and beyond workers”. In the online community’s library, suggested readings include philosopher Bertrand Russel’s In Praise of Idleness; anthropologist David Graeber’s rant on bullshit jobs; and even “Fiction with Anti-Work Themes” including Herman Melville’s Bartleby, the Scrivener. Overarching the subreddit discussions is the Keynesian dream of a future in which technological innovation and efficiency gains would usher “a golden age of leisure” with a 15-hour work week – a post-work imaginary where creativity and productivity are not monopolized by the employment relation, that is, waged labor. “A lot of people mistake antiwork for being lazy, and like nothing has to ever get done,” says u/rockcellist, a moderator of the subreddit. “But the truth of the matter about antiwork … is that obviously things have to get done, but the current structure in which things get done and the way that capital flows as they get done is unfair and should be nonexistent.”

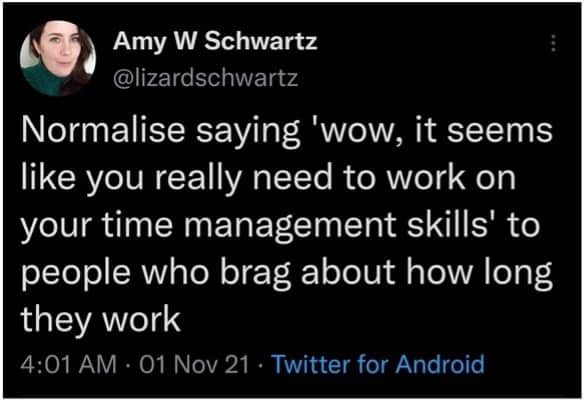

Twitter witnessed a viral “Nobody Wants to Work Anymore” meme, kickstarted by a worker uploading a video of a McDonald’s drive-thru sign reading: “We are short-staffed. Please be patient with the staff that did show up. Nobody wants to work anymore.” The meme triggered an avalanche of pictures of similar signs from businesses across the country, eliciting a broader conversation on worker exploitation that immediately outgrew the service industry. Lucidly capturing the internet’s pulse, former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich tweeted: “Let’s get one thing straight: there is no labor shortage. There is a shortage of employers willing to pay their workers a living wage. Instead of: no one wants to work anymore. Try: no one wants to be exploited anymore.”

Tik Tok’s #burnouts section attracted 205 million views, fueling withering commentary on the futility and frustration of toiling away for long hours at “bullshit jobs”, mostly by youth. In May, well-known Youtuber Katherout posted a video entitled “I no longer aspire to have a career”, triggering a wave of similar commentary from young influencers skeptical of careerism.

Offline Backdrop: Topsy-Turvy Job Market Post-Covid

This moment of internet solidarity is not happening in a digital vacuum. It aligns with an offline growth in union membership in the US throughout Covid – as well as the highest approval rate of labor unions in fifty years. It must be understood against the backdrop of the “Great Resignation”, as disillusioned workers quit their jobs en masse – fed up with wages that have been on the decline for decades, while student debt rises, and inequality widens.

Nearly every industry is struggling with labor shortage as people refuse returning to the grind for as long as they can afford to do so. The latest U.S. labor statistics expect the global shortfall at 40 million skilled workers, with forecast losses of trillions if current trends continue. Meanwhile, hiring managers are complaining of workers not showing up to their first day on the job, let alone applicants to scheduled interviews.

In just 18 months, Covid laid bare much of what wasn’t working about work. Low-wage workers are now “essential”, to be celebrated, not undervalued. Diminished is the “everyday I’m hustling” mentality, in favor of a new conventional wisdom: “You don’t have to be productive during a pandemic.”

To what extent, if at all, does this trend signal a cultural shift in our conception of work? Does it run deeper than a desire for change of employment conditions, to dissatisfaction with the very nature of work under late capitalism? Cautious optimism is warranted – and there has arguably never been a better time to reimagine our relationship to “work”, insofar as we mean selling our labor for wages. Here are two ways to frame the ideas floating around the digital public sphere.

1. Career Skepticism or Rejection of Internalized Capitalism

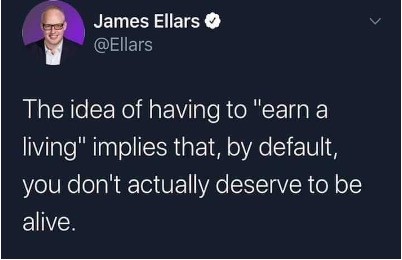

Careerism, to be sure, has long been a pejorative word, associated with superficial ladder climbing mentality. The new strand of career skepticism emerging on the internet is different. It is not condemnation of how one navigates the game of work, it is a rejection of the game itself. Consider Youtuber Katherout’s framing: “Jobs aren’t designed for you to love them. That’s not the point. The point is to give you income so you can participate in society and most people can’t accept that.”

The questions career skeptics ask are straightforward: what if, instead of hustling towards a career goal for decades and barely tolerating day-to-day rough patches, we created a different value system around labour? What if the resume at the end of a worker’s life was not a measure of their worth – or reflection of their identity? What if work was not a means to an end?

Skeptical workers can find support in several scholars. In his new book, Work: A History of How We Spend Our Time, anthropologist David Suzman explains how capitalist society depoliticized the conception of work; how we accept waged work as a naturalized, inevitable mechanism for income distribution, as well as a means of defining citizens as social and political subjects. His work (pun intended) echoes an earlier book by gender studies scholar Kathi Weeks, The Problem with Work, who argues that the assumptions about human nature underpinning market society – that we are competitive by nature, with desires exceeding our scarce means – are simply not borne out by modern psychology, nor history.

2. Unemployment for All, Not Just the Rich!

The #antiwork movement organically aligns with today’s unprecedented interest in universal basic income (UBI), a possible solution to redress a work-life balance skewed beyond proportion. But UBI’s potential isn’t limited to emancipation within waged work. It could arguably shift power relations between waged and unwaged workers, performing crucial “work” in families and communities. This reflects sociologist Erik Olin Wright’s embrace of UBI as “eroding capitalism” over time. What UBI could effectively translate into is an emancipatory right to refuse the waged labor market itself.

Times They Are a-Changin

In our era of unparalleled economic inequality, #antiwork presents a hopeful idea: maybe it doesn’t have to be like this. Maybe, just maybe, work can work for us. It is said the revolution will not be televised, but could it begin on Twitter?

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

December 11

In today’s News and Commentary, Biden’s NLRB pick heads to Senate vote, DOL settles a farmworker lawsuit, and a federal judge blocks Albertsons-Kroger merger. Democrats have moved to expedite re-confirmation proceedings for NLRB Chair Lauren McFerran, which would grant her another five years on the Board. If the Democrats succeed in finding 50 Senate votes […]

December 10

In today’s News and Commentary, advocacy groups lay out demands for Lori Chavez-DeRemer at DOL, a German union leader calls for ending the country’s debt brake, Teamsters give Amazon a deadline to agree to bargaining dates, and graduates of coding bootcamps face a labor market reshaped by the rise of AI. Worker advocacy groups have […]

December 9

Teamsters file charges against Costco; a sanitation contractor is fined child labor law violations, and workers give VW an ultimatum ahead of the latest negotiation attempts

December 8

Massachusetts rideshare drivers prepare to unionize; Starbucks and Nestlé supply chains use child labor, report says.

December 6

In today’s news and commentary, DOL attempts to abolish subminimum wage for workers with disabilities, AFGE reaches remote work agreement with SSA, and George Washington University resident doctors vote to strike. This week, the Department of Labor proposed a rule to abolish the Fair Labor Standards Act’s Section 14(c) program, which allows employers to pay […]

December 4

South Korea’s largest labor union began a general strike calling for the President’s removal, a Wisconsin judge reinstated bargaining rights for the state’s public sector workers, and the NLRB issued another ruling against Starbucks for anti-union practices.