Dr. David Doorey is a Professor of Labor and Employment Law at York University in Toronto.

Rawan Abdelbaki is a PhD Candidate in Sociology at York University in Toronto.

Not very often do events in Canada make global headlines. The recent protest convoy that occupied Ottawa for several weeks in February and shut down international borders proved the exception to the rule. The organizers of the protest were a mishmash of right-wing insurrectionists and QAnon delusionists seeking to end vaccine mandates, charge Prime Minister Trudeau with treason, and overthrow the federal government. As the number of supporters grew and Canadians learned more about its leaders, a narrative emerged that the convoy was a peaceful grassroots movement of the “working class” fed up with government overreach. The Nazi and Confederate flags and calls for the government to be forced out of office were dismissed as the work of a few bad apples.

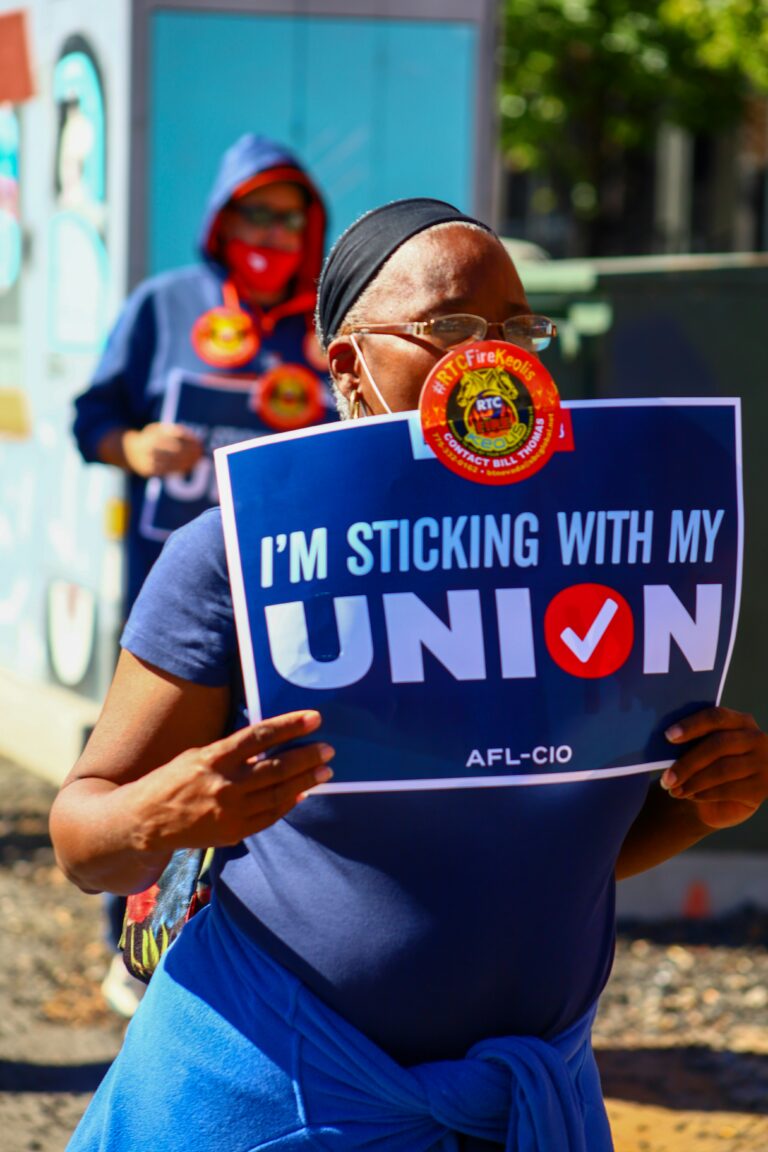

Meanwhile, the Canadian labor movement took exception to protesters’ claim that this was a working-class movement. While unions sometimes disagreed on the introduction of mandatory vaccination policies by employers, they were united in opposition to the tactics of the convoy and the racist and undemocratic goals of the movement and its leaders, even if concerns remain about the governments’ use of emergency legislation to quash the protest.

Canadian Labor’s Response to Workplace Vaccination Policies

The response to mandatory workplace vaccination policies within the Canadian labor movement has not been uniform. Some unions challenged mandatory vaccination policies, arguing that terminating unvaccinated workers went too far and that regular COVID-19 testing was a more reasonable and measured response. Other unions supported mandatory vaccine policies at work provided that accommodations were made for workers with legitimate reasons for not being vaccinated.

The mixed response of unions to workplace vaccine mandates is partially explained by the legal framework that governs the relationship between unions and the workers they represent. As in the United States, Canadian unions have a legal “duty of fair representation.” That duty is statutory in most provinces and applies to collective bargaining and grievance administration. In practice, it is not very difficult for unions to satisfy the DFR standard. For example, a union can withdraw a grievance filed by an employee terminated for noncompliance with a mandatory vaccination policy and that decision would not violate the DFR, provided that the union considered the merits of the grievance in good faith. However, a union that supported a mandatory vaccination policy that automatically led to the termination of all unvaccinated employees could leave itself exposed to DFR liability insofar as some employees may have a legitimate basis for refusing the vaccine.

A second point to understand about Canadian labor law is that there was arbitration case law considering the legality of mandatory vaccination policies in unionized workplaces long before COVID-19. Therefore, unions and employers had a pretty good idea of how a grievance challenging the application of a COVID-19 vaccination policy would be dealt with by labor arbitrators. Canadian labor arbitrators long ago implied a restriction on the right of unionized employers to unilaterally impose new workplace rules. This restriction — known as the KVP Test after the leading case — permits only the introduction of rules that are not inconsistent with the collective agreement and that are “reasonable”.

Determining whether a rule is reasonable requires a contextual analysis that considers all the circumstances, including whether a particular policy infringes upon the privacy of employees more than is necessary to achieve a reasonable business or public health goal. The arbitration results on mandatory vaccination policies are mixed. Canadian arbitrators have ruled some vaccination policies to be unreasonable in the circumstances and others to be reasonable and within the scope of management rights. Given the uncertainty regarding the legality of vaccine policies, combined with the DFR obligation imposed on unions to consider each grievance on its merits and union leaders’ desire to appear to be taking vaccine-resistant member concerns seriously, it was not surprising that some unions opted to challenge employer vaccination policies and let arbitrators determine their legality.

Labor’s Response to the Protests and Blockades

While Canadian unions sometimes disagreed on their responses to mandatory vaccination policies at the workplace, organized labor’s reaction to the blockades and protests against government-imposed vaccine mandates and other public health measures was uniformly one of condemnation.

For example, Teamsters Canada described the convoy as a “despicable display of hate led by the political right” and decried the protesters’ actions as inconsistent with the values of the Union and “the vast majority” of its members, many of whom had lost work due to the border blockades. Unifor (formerly the Canadian Auto Workers) noted that while it respects the important role of protest and freedom of expression, the convoy was a movement of “right-wing extremists” that mirrored the insurgents that had attacked the U.S. Capitol last year. The president of the Canadian Union of Public Employees denounced the “anti-vaccine, anti-science protesters” who bullied hard-working Canadians while displaying “deplorable symbols of hate and bigotry.” The Canadian Union of Postal Workers announced that it supported “principled non-violent demonstrations oriented toward positive social change,” but asserted that the convoy had veered far from this ideal by supporting fascism and the overthrow of a democratically elected government.

Canada’s umbrella labor confederations similarly spoke out against the protesters and blockades. The Canadian Labour Congress rejected the protesters’ goals, which as noted earlier included not only an end to vaccine mandates but also a call to overthrow the federal government. A Joint Statement from Canada’s Unions concluded that “Canada’s unions stand together, unequivocally opposed to these vile and hateful messages and condemn the ongoing harassment and violence against the people of Ottawa.” The Ontario Federation of Labour emphasized that the protests were not worker-led: “Workers are not being championed by these lawless mobs, they are victims. Workers are being harassed and bullied for trying to stay safe while doing their job. Canadian unions uniformly opposed the border blockades that led to closures of many businesses and the layoff of thousands of workers.”

Given the racist and antidemocratic motives behind the recent protests that occupied Canada’s capital for several weeks, it was not likely a difficult decision for Canadian unions to publicly condemn the movement. When the protesters then shut down the Canada-U.S. border for an extended period, causing massive economic disruption and harm to thousands of workers on both sides of the border, it made sense for unions to condemn the blockades.

However, just as unions balanced competing concerns in their responses to employer vaccination policies, the labor movement’s united opposition to the convoy and blockades involved a calculated risk. Some unions have expressed concern about the precedent set by the Liberal government in implementing the Emergencies Act to quash the protest. For example, the leadership of Ontario’s largest public-sector union voted to oppose the use of the Emergencies Act, observing that “the labour movement has often been the target of legislation aimed at suppressing anti-government dissent.” It does not take much imagination to envision conservative politicians pointing gleefully to the Liberals’ use of emergencies legislation to justify future crackdowns on labor leaders and legitimate social protests. It will be crucial moving forward that political leaders and police recognize and respect a clear distinction between fascist protests calling for the overthrow of democratically elected governments and legitimate labor and social protest.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

December 18

New Jersey adopts disparate impact rules; Teamsters oppose railroad merger; court pauses more shutdown layoffs.

December 17

The TSA suspends a labor union representing 47,000 officers for a second time; the Trump administration seeks to recruit over 1,000 artificial intelligence experts to the federal workforce; and the New York Times reports on the tumultuous changes that U.S. labor relations has seen over the past year.

December 16

Second Circuit affirms dismissal of former collegiate athletes’ antitrust suit; UPS will invest $120 million in truck-unloading robots; Sharon Block argues there are reasons for optimism about labor’s future.

December 15

Advocating a private right of action for the NLRA, 11th Circuit criticizes McDonnell Douglas, Congress considers amending WARN Act.

December 12

OH vetoes bill weakening child labor protections; UT repeals public-sector bargaining ban; SCOTUS takes up case on post-arbitration award jurisdiction

December 11

House forces a vote on the “Protect America’s Workforce Act;” arguments on Trump’s executive order nullifying collective bargaining rights; and Penn State file a petition to form a union.