Joshua Olszewski-Jubelirer is a student at Harvard Law School.

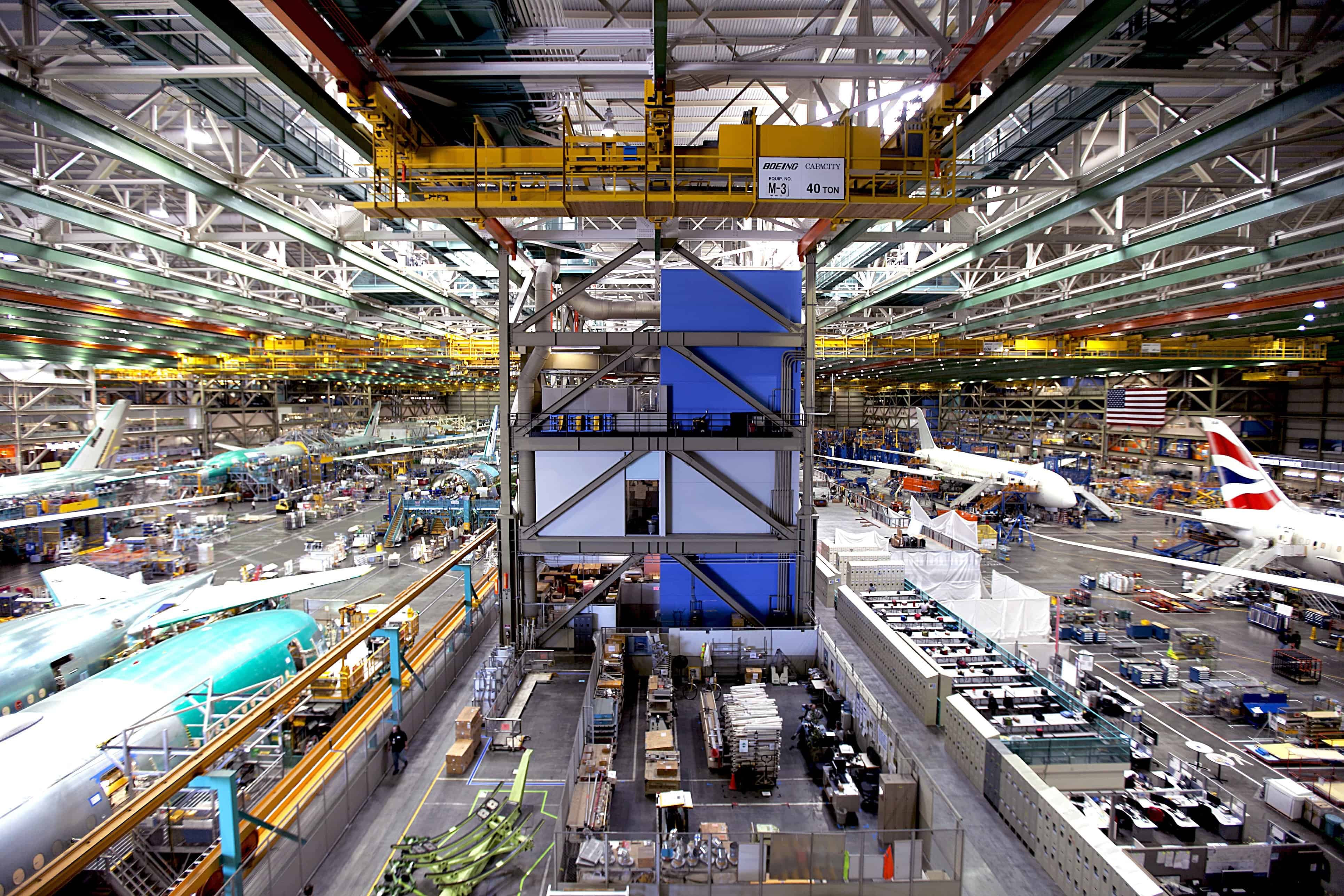

In The Boeing Company, 365 NLRB No. 154 (2017), the Trump majority wrapped itself in the guise of responding to the #MeToo movement to justify overturning Board precedent governing workplace civility codes. Their holding that civility codes are presumptively lawful seriously discounts the chilling effect that overly broad civility rules can have on workers considering exercising their Section 7 rights. However, there is a distinct problem with one corner of labor law and sexual harassment: the rules governing speech on the picket line inappropriately privilege Section 7 rights over employees’ rights under anti-discrimination law to be free from harassment based on protected categories. The Boeing Company may signal that the Board is eager to address this imbalance soon by bringing picket line rules into line with the rest of labor law.

First, let’s review the Board’s decision in The Boeing Company. For the 13 years before the decision, the Board had held that a workplace rule that does not explicitly prohibit Section 7 activity nonetheless illegally “interferes” with employees’ Section 7 rights if “employees would reasonably construe the language to prohibit Section 7 activity.” As Sharon Block has detailed, the Board in The Boeing Company decided that this standard, announced in a 2004 case named Lutheran Heritage Village-Livonia, was too difficult to consistently apply, and had led to the Board ordering employers to eliminate common sense policies that require employees to “‘work harmoniously’ or conduct themselves in a ‘positive and professional manner.’” Instead, the Boeing Board set up a balancing test, where the Board would weigh “the potential adverse impact” of the workplace rule on Section 7 rights against the employer’s business justifications.

The Boeing Board specifically made clear that “rules requiring employees to abide by basic standards of civility” are lawful in all cases. In doing so, the Boeing Board overruled the Board’s 2016 decision in William Beaumont Hospital, where the panel ordered a hospital employer to revise or eliminate rules in its employee handbook that prohibited “[c]onduct . . . that impedes harmonious interactions and relationships” and “negative or disparaging comments about the . . . professional capabilities of an employee. . ..”

In addition to a professed need for predictability in the law, the Boeing Board justified its decision to uphold civility codes based on a desire to protect workers from “intimidation, profanity, harassment, or even workplace violence” that may result if employers shy away from requiring respectful treatment. Indeed, the majority posited, rather implausibly, that workplace rules governing harassment that are required to avoid Title VII liability could have been found unlawful under Lutheran Heritage. Arguments against broad workplace civility rules “reflect stereotypes regarding workplace conduct and protected activity that fail to adequately address problems [that] have become more prominent in recent years—indeed, in recent weeks.” Overruling Lutheran Heritage was merely “‘adapt[ing]’ our statute to ‘changing patterns of industrial life.’” That is, to the rampant sexual harassment that the #MeToo movement has revealed “in recent weeks.”

What possible impact would general workplace civility rules have on sexual harassment? Even under Lutheran Heritage, employers were able to explicitly ban harassment and other specific speech and conduct that could violate workers’ Title VII rights. The best argument goes something like this: broad workplace rules discourage employees from saying or doing things that might conceivably violate the rules. Indeed, this “chilling effect” is exactly why the Board has been concerned with workplace rules that don’t explicitly prohibit Section 7 activities. Under this logic, the broader the rule, the more likely that it will discourage employees from objectionable conduct that gets close to harassment. Or perhaps the Boeing Board had in mind the 2016 Report of the EEOC’s Select Task Force on the Study of Harassment in the Workplace, which cited testimony from experts that incivility is correlated with gender-based harassment, and that “uncivil behaviors can often ‘spiral’ into harassing behaviors.”

Rather than protecting workers from harassment, the Boeing Board’s approval of overbroad civility codes is likely to harm workers’ ability to build power that they can use to protect themselves from harassment. If an employer writes a workplace rule requiring employees to refrain from conduct that “impedes harmonious interactions or relationships,” a certain proportion of employees are likely to believe that the rule means that they could be fired for complaining about how they are treated at work, including “uncivilly” complaining about sexual harassment, as Member McFerran argued in dissent. The Lutheran Heritage standard merely required employers to make their rules clear enough that a reasonable employee would not make that incorrect assumption, by giving specific examples of prohibited conduct, or by explicitly informing employees of their Section 7 rights and laying out how the rules did not interfere with those rights. Employers can require respectful interactions in the workplace, so long as they also clearly affirm their employees’ rights to engage in protected concerted activity.

Nevertheless, the spirited back-and-forth in The Boeing Company about workplace harassment points to an unresolved tension between labor law and employment discrimination protections. The Board often protects individual workers who engage in racial or sexual harassment in the course of exercising their Section 7 rights on the picket line. In doing so, it protects the ability of those workers to use their voices to silence women, people of color, and members of other protected groups, in the workplace.

It is true that in the context of protected concerted activity outside of the picket line, the Board applies a standard that is considerably more deferential to employers who discipline their employees for making racial or sexually harassing comments. For example, the Board approved Honda’s right to discipline an employee who used his pro-union newsletter to challenge an anti-union employee to “come out of the closet.” And the General Counsel’s Division of Advice recently recommended approving Google’s decision to fire James Damore for sexually discriminatory statements in his infamous memo, on the grounds that the company had a right to enforce its sexual harassment policy.

On the picket line, however, the Board applies a standard that is much more protective of employees’ concerted activities, leaving employers with no ability to discipline striking workers who engage in egregious sexual and racial harassment. This standard for so-called striker misconduct from Clear Pine Mouldings asks merely whether the conduct “may reasonably tend to coerce or intimidate [other] employees in the exercise of rights protected under the Act,” which is to say, to coerce non-striking employees to forgo their right to not strike. Under this standard, the Board in 2016 ordered reinstatement for a striking worker who yelled after a van carrying black replacement workers drove into the factory, “Hey, anybody smell that? I smell fried chicken and watermelon,” reasoning that his racist taunting was not threatening, and that the replacement workers had already passed by when he yelled at them. An ALJ applying this standard held that the company could not fire a striking worker for standing in front of a non-striking white woman worker’s car, and yelling “You f—in’ bitch, n—– lovin’ whore.”

Several commentators, including D.C Circuit Judge Millett, have called for the Board to address this tension by making clear that racial and sexual harassment by employees are not protected by the NLRA, even in the course of a strike. The Boeing Board’s professed concern for protecting employees from harassment suggests that they may be eager to bring striker misconduct rules into line with the rest of labor law in this way. For a Trump majority that is inclined to take better account of the interests of business, this move would have an added benefit: giving employers more ability to discipline pro-union employees.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

April 18

Disneyland performers file petition for unionization and union elections begin at Volkswagen plant in Tennessee.

April 18

In today’s Tech@Work, a regulation-of-algorithms-in-hiring blitz: Mass. AG issues advisory clarifying how state laws apply to AI decisionmaking tools; and British union TUC launches campaign for new law to regulate the use of AI at work.

April 17

Southern governors oppose UAW organizing in their states; Florida bans local heat protections for workers; Google employees occupy company offices to protest contracts with the Israeli government

April 16

EEOC publishes final regulation implementing the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act, Volkswagen workers in Tennessee gear up for a union election, and the First Circuit revives the Whole Foods case over BLM masks.

April 15

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of bakery delivery drivers in an exemption from mandatory arbitration case; A Teamsters Local ends its 18-month strike by accepting settlement payments and agreeing to dissolve

April 14

SAG-AFTRA wins AI protections; DeSantis signs Florida bill preempting local employment regulation; NLRB judge says Whole Foods subpoenas violate federal labor law.