Brianne Power is a student at Harvard Law School.

In the past few years, criminal justice debt has received growing attention from legal scholars and advocates. The term “criminal justice debt,” also known as “legal financial obligations (LFOs)” or simply “fines and fees,” refers to the financial obligations imposed on individuals accused or convicted of a crime or infraction as they navigate the criminal justice system. These financial obligations include “fines,” monetary penalties for crimes and infractions, and “fees,” monetary obligations charged for the costs of “participating in” the criminal justice system. Depending on the state, fees may be charged for court costs, public defendant recoupment, costs of imprisonment, and costs of probation and parole, among others.

The Supreme Court has consistently found jailing individuals due to an inability to pay off debt unconstitutional. In Williams v. Illinois (1970), the Court held that the Equal Protection Clause precludes states from extending prison sentences beyond statutory maximums due to a defendant’s inability to pay a fine. The following year, in Tate v. Short (1971), the Court held that converting a fine to a prison sentence due to inability to pay also violated the Equal Protection Clause. In Bearden v. Georgia (1983), the Court held that the Equal Protection Clause and Due Process Clause require courts to consider an individual’s ability to pay and the adequacy of alternative punishments before revoking an individual’s probation and sending them to prison for failure to pay a fine. However, despite this precedent, scholars and advocates report that individuals continue to be jailed due to an inability to pay fines and fees, resulting in what some call “modern day debtor’s prisons.” Even more troubling, like many aspects of our criminal justice system, the burdens of criminal justice debt and modern day debtor’s prisons fall disproportionately on communities of color.

Community service programs have largely been lauded as a progressive alternative to modern day debtor’s prisons. These programs, like this one in Charlottesville, Virginia, “compensate” individuals for community service work by reducing the money they owe in fines and fees. Proponents of the community service alternative include Harvard’s Criminal Justice Policy Program and the Department of Justice under former President Obama. (Attorney General Sessions has since rescinded the 2016 DOJ guidance on criminal justice debt.) Massachusetts is currently considering implementing a similar program, proposed by Governor Charlie Baker.

However, while these reforms are targeted at eliminating unconstitutional practices, they raise new constitutional questions. As Professor Noah Zatz notes, “when low-income communities, of disproportionately people of color, are offered incarceration as the alternative to work, Thirteenth Amendment jurisprudence should go to high alert.” For an individual unable to pay off criminal justice debt, providing community service as an alternative to jail simply changes the available options from jail time to jail time or work, presenting a paradigmatic forced labor violation. Thus, in some applications, these programs may contravene the Thirteenth Amendment.

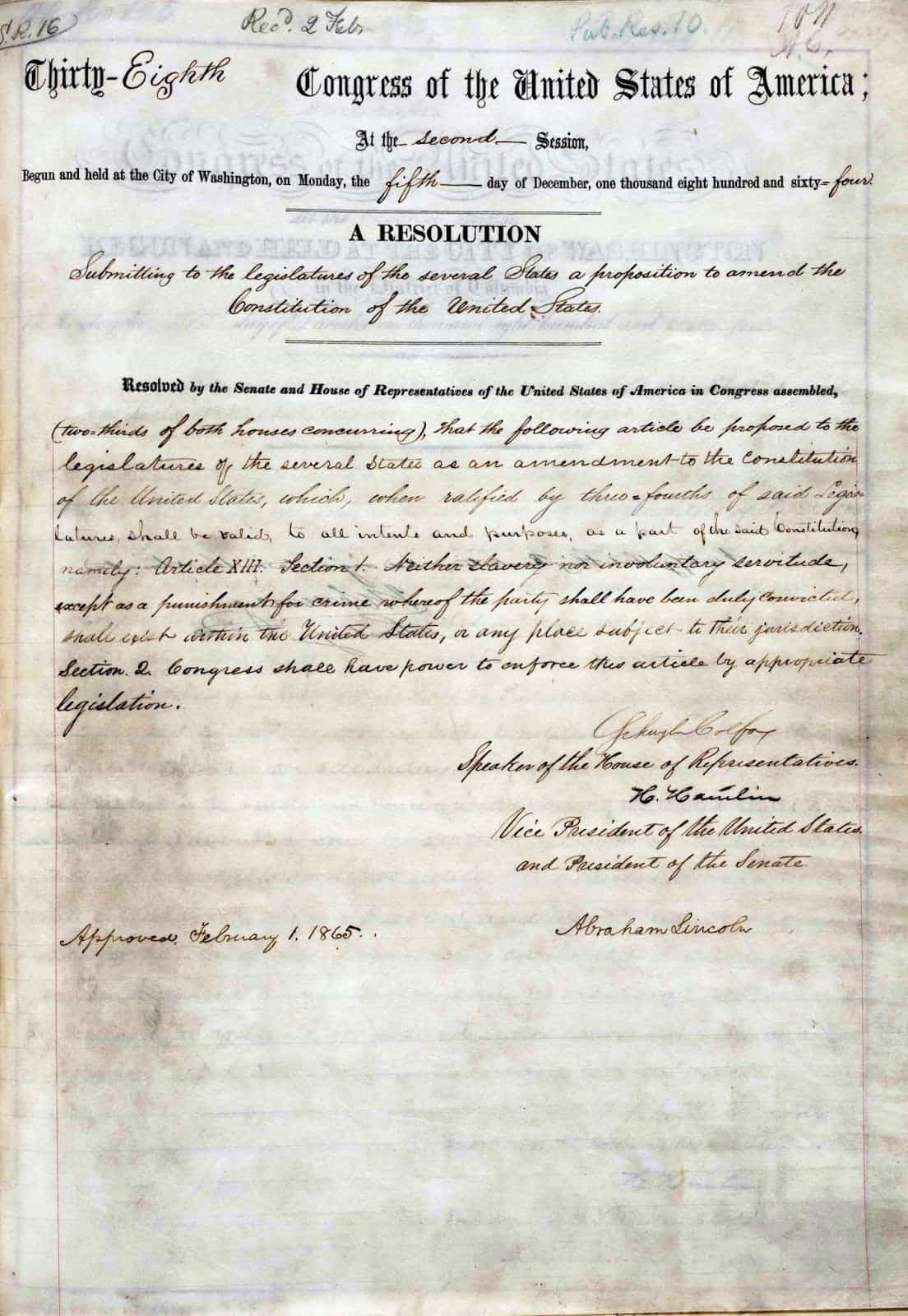

The Thirteenth Amendment prohibits both slavery and involuntary servitude. In Pollock v. Williams (1944), the Supreme Court explained, “[t]he undoubted aim of the Thirteenth Amendment. . .was not merely to end slavery but to maintain a system of completely free and voluntary labor throughout the United States.” Speaking directly to scenarios in which individuals work to pay off debt, the Court elaborated, “[w]hatever of social value there may be, and of course it is great, in enforcing contracts and collection of debts, Congress has put it beyond debate that no indebtedness warrants a suspension of the right to be free from compulsory service.”

However, assessing the constitutionality of these programs becomes difficult in light of the complicated jurisprudence surrounding the Thirteenth Amendment. The Thirteenth Amendment does not ban all compulsory service. There is a textual exception for labor performed “as punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted,” and courts have crafted a few additional, narrow albeit amorphous exceptions.

In light of these complications, these programs present a number of constitutional questions:

1) Could this community service be considered labor performed “as punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted?”

To address this question, we must first return to the distinction between fines and fees. Recall that “fines” are monetary penalties for crimes and infractions, while “fees” are charges accrued for costs of “participating in” the system.

Since fees are not considered “punishment,” there is no colorable argument that labor to pay them off falls under the duly convicted exception. Such labor would be unconstitutional unless it falls under one of the judge-made exceptions, described below.

On the other hand, fines, which generally are considered punishment, present a closer constitutional question. It seems relatively clear that fines assessed for non-criminal violations (like traffic citations) would not fall under this exception, as they are not “crimes” and offenders are not “convicted.” There are instances, however, where fines are levied “as punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” In such instances, the constitutionality of forced labor to pay off such fines would depend on the connection between the labor and the penalty. While courts have not addressed this question, advocates could argue that the labor is too far removed to be considered punishment for the crime.

This analysis is further complicated by a lack of transparency about how fines and fees are imposed and the ways in which they may be intertwined. The lack of transparency is so severe that individuals facing criminal justice debt may not even have access to information about their financial obligations and the legal basis for their imposition. Thus, while separating fines and fees is necessary to analyze the constitutionality of labor to pay them off, they may not be easily separable in any individual instance.

2) Could this community service fall under one of the amorphous judge-made exceptions?

As explained in more detail here, courts have created additional exceptions for certain “special circumstances.” These circumstances include work compelled of children by their parents or apprenticeship masters and a category of services historically treated as exceptional. This later exception is amorphous and ill-defined. While some lower courts have interpreted it broadly to include “civic duties” owed to the public, the Supreme Court has limited this category to “services which have from time immemorial been treated as exceptional.” This category includes jury service, military service, contracted work on ships, and, oddly enough, work on public roads.

Because these programs have only recently been created, it’s hard to imagine they would fall into this exception reserved for historically exceptional services. However, states and municipalities could argue that their programs fall within this exception based on lower courts’ more expansive interpretations. Assuming courts follow the Supreme Court’s more conservative approach, we are left with questions about whether the program could survive in certain forms. For example, one could imagine a program in which individuals only preform work on public roads.

3) Can these programs be crafted to avoid potential constitutional violations?

Providing a program in which individuals unable to pay off their criminal justice debt can work it off through community service is not inherently unconstitutional or undesirable. The constitutional questions arise only when work and jail are the only available options. To alleviate constitutional concerns, advocates and policymakers should pair community service programs with less constitutionally suspect alternatives, such as waiving fines and fees, crediting individuals for engaging in programs and treatment, or giving judges discretion to create individualized sanctions that do not involve work or jail.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

April 19

Alabama and Louisiana advance anti-worker legislation; Mercedes workers in Alabama set election date; VW Chattanooga election concludes today.

April 18

Disneyland performers file petition for unionization and union elections begin at Volkswagen plant in Tennessee.

April 18

In today’s Tech@Work, a regulation-of-algorithms-in-hiring blitz: Mass. AG issues advisory clarifying how state laws apply to AI decisionmaking tools; and British union TUC launches campaign for new law to regulate the use of AI at work.

April 17

Southern governors oppose UAW organizing in their states; Florida bans local heat protections for workers; Google employees occupy company offices to protest contracts with the Israeli government

April 16

EEOC publishes final regulation implementing the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act, Volkswagen workers in Tennessee gear up for a union election, and the First Circuit revives the Whole Foods case over BLM masks.

April 15

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of bakery delivery drivers in an exemption from mandatory arbitration case; A Teamsters Local ends its 18-month strike by accepting settlement payments and agreeing to dissolve